We hear from many clients who feel apprehensive when they start spending their retirement savings. It can feel unnatural after you’ve been focused on saving for decades. Or… maybe you can’t wait to spend!

Either way, it’s critical that you make the transition from saving to spending using strategic retirement income withdrawal strategies, ultimately prolonging your retirement income.

Understand the four most common retirement income withdrawal plans, including the merits and flaws of each. Read our special report.

Planning Ahead

When it comes to investing and retirement, most of the emphasis is placed upon saving enough, but there’s another crucial element to plan for: Spending. Just as a retirement savings plan is essential in building a nest egg, a retirement spending plan is equally important in making sure your money doesn’t run out too soon.

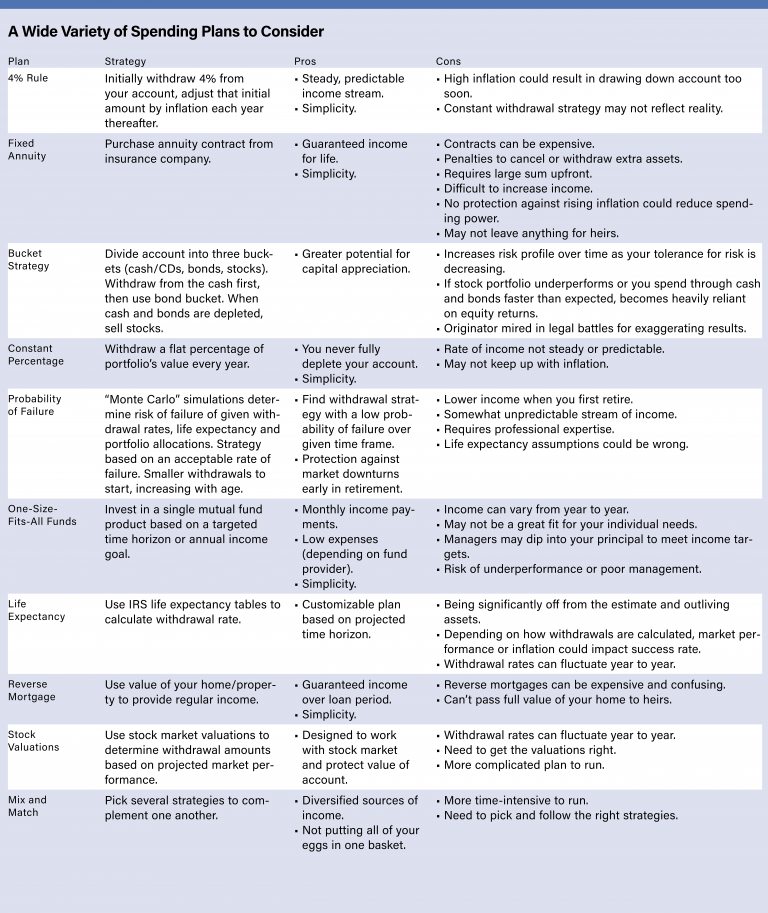

This special report, available exclusively from Adviser Investments, analyzes the merits and flaws of some of the more common retirement withdrawal plans we’ve come across, including:

- The “4% Rule,” which calls for withdrawing 4% annually upon retirement

- A fixed annuity strategy that guarantees income for the entirety of your retirement years

- The “Bucket Strategy” that divides stocks, bonds and cash into separate subsets

- The “Constant Percentage Method” of withdrawing a set amount per year

- … And more!

Whether it’s maintaining the same quality of life, beginning a new hobby, traveling more or leaving an estate for your heirs, how you manage your spending as well as your investing in retirement can mean the difference between a lifestyle free from worry and sleepless nights.

At Adviser Investments, we find that when it comes to retirement, writer H.L. Mencken’s aphorism is apt: “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong.”

Traditional spending strategies that may have worked in the past may no longer do so in the current economic and market environment. For one thing, with bond yields as low as they are, the presumed safety and income that an ever-growing allocation to bonds would have provided in years past is far from guaranteed today.

Plus, newer strategies and investment products worthy of consideration have emerged over the years. In our 25 years of partnering with clients to reach their retirement goals, we’ve found the best way to approach this complex and personal subject is to work with a trusted financial adviser who can guide you through the options and develop a strategy that best fits your individual spending flexibility and needs.

This report reviews the merits and flaws of a number of the more popular retirement withdrawal plans we’ve encountered. We believe it will help prepare you for the most meaningful financial conversation you can have about your retirement—a conversation that your wealth management team at Adviser Investments would be happy to have with you.

The 4% Rule

Let’s begin with one of the simplest approaches we’ve uncovered. William Bengen’s 4% rule, introduced in a 1994 Journal of Financial Planning article, is a widely accepted strategy that involves withdrawing 4% of assets from a balanced 60/40 stock/bond portfolio upon retiring, and continuing to take out that initial amount (not necessarily 4% of the portfolio) adjusted by the rate of inflation each year thereafter.

The appeal of this approach: Simplicity and the consistent stream of income generated. The downside? Your retirement account could run out of money prematurely, especially when faced with a significant market downturn.

Bengen derived the 4% figure by gathering historical market returns and inflation data going back to 1926. He then modeled the effects of a person retiring each year onward to see how long these hypothetical retirees’ nest eggs would have lasted given different economic environments, market climates and withdrawal rates. Bengen found that for a retiree with a 30-year time horizon, the highest withdrawal rate that never completely depleted the portfolio was 4%.

Of course, just because a strategy worked in the past doesn’t mean it will work in the future (and there is mounting evidence that this may be the case with the 4% rule as Bengen initially laid it out). While Bengen’s data encompassed many market cycles, which featured periods ranging from depression to mania and deflation to rapid inflation, a significant criticism was his U.S.-only focus— the U.S. stock market has been one of the best long-term investments over the last century.

We think the U.S. stock market will continue to be among the best investments for long-term investors. However, a changing dynamic between stocks and bonds could result in adherents of the 4% rule becoming unable to maintain an acceptable level of income or drawing down their account too soon.

Alternatively, for some, the 4% rule may be too conservative. Bengen’s original study only included large-cap U.S. stocks and high-quality U.S. bonds held in a balanced portfolio. Adding other asset classes (such as small-cap or foreign stocks, commodities or high-yield bonds) or using a more aggressive stock/bond mix could potentially increase gains over time and thus the acceptable withdrawal rate. If your time horizon for drawing down your account is less than 30 years, the 4% rule may also be too frugal.

Reflecting the shifting-target nature of this kind of planning, Bengen has had to adapt his strategy a number of times over the years. At one point he recommended a 4.5% initial withdrawal, and he also began advising that investors include a broader mix of investments to increase diversification and return potential.

Other issues arise with the 4% rule as well. It assumes spending patterns are constant throughout retirement. In reality, you may want to spend more early on and less in the later years. The unfortunate possibility also exists that you may be faced with unexpected expenses. Or you could spend less money in your early years and much more in medical expenses in your later years. In running backtests, it is easy to be a disciplined investor. But 30 years is a long time for an individual investor to stick to a single, strictly rule-based withdrawal strategy.

On the surface, the 4% rule is appealing in its simplicity— in combination with a good long-term investment plan, it could see you through retirement. Still, there are quite a few other possible solutions to consider as well.

Fixed Annuity

Fixed annuities have become a popular retirement investment vehicle, particularly for risk-averse investors. In essence, fixed annuities are insurance products. In exchange for an upfront lump-sum payment, the annuity’s underwriter offers a guaranteed stream of income throughout retirement, no matter how long you live or how poorly the markets perform. The appeal of an annuity is that it sets a floor on the amount of income your portfolio generates. It also removes “longevity risk”—the chance you will outlive your income stream.

But annuities aren’t always what they are cracked up to be. With an annuity, your money is tied up (with hefty penalties for early withdrawals or canceling the contract) and you have limited potential to increase your income. And a fixed annuity means that your heirs may not receive anything from it unless you pay extra for a death benefit option. (For this reason, some investors are turning to variable annuities to fill a similar role. Annuities of this type couple the insurance component with various investment options, leaving more opportunity to pass the value of the investment on to the next generation.)

Insurance companies charge high fees for taking on the risk of providing you with income for life, and that guarantee is only as good as the insurance company behind it. Keep in mind that in the current low-interest-rate environment, it may take a large initial investment to generate a sufficient level of income from a fixed annuity. And finally, unlike the 4% rule, which increases your withdrawals with inflation, the amount of income you receive here is fixed. If inflation picks up (prices rise), there is no guarantee that the payouts from your annuity will support your future spending.

The Bucket Strategy

In 2004, author and financial adviser Ray Lucia wrote Buckets of Money: How to Retire in Comfort and Safety, outlining his approach to retirement withdrawals. (It should be noted that in 2012 the SEC charged Lucia with misrepresenting the success of his “buckets” approach. He has since faced a number of legal challenges; his appeal is pending.) In the book, Lucia advised retirees to separate their retirement portfolio into three subsets, or “buckets.” The first bucket consists of safe, liquid investments such as cash and CDs. The second bucket contains somewhat riskier assets like intermediate-term corporate bonds. The third bucket holds stocks, the riskiest assets in the portfolio.

Retirees withdraw from the first bucket (cash and CDs) at the beginning of retirement, thus allowing the riskier buckets to grow. When the cash bucket has been depleted, it is refilled from the riskier bond bucket. (Ideally, a retiree would run out of cash and CDs just as the bonds in the second bucket start to mature, allowing a seamless transition into cash for retirement spending needs.) When the first two buckets are drained, they are refilled by the third bucket (stocks).

Lucia argued that you should withdraw from the safest assets in the portfolio first to allow the maximum amount of time for stocks to grow before being depleted. The cash and bond buckets should last through at least the first 15 years of retirement, which would hopefully give the equity bucket enough time to recoup any short-term losses caused by bear markets.

The downside is that a retiree’s overall portfolio risk increases as the ability to suffer short-term losses decreases. Lucia’s strategy doesn’t allow much room for error or unexpected lifestyle changes. If the equity market does not perform as well as expected over the first 15 years of retirement, an 80-year-old investor may find himself in the precarious situation where he is 100% invested in equities (having depleted his first two safer buckets) and his stock portfolio hasn’t grown as large as he had expected. Any short-term drop in the stock market could cause irreparable harm to his quality of life.

Similarly, if forced to deplete the two less risky buckets faster than expected, a retiree would be 100% invested in equities without enough time for the stock bucket to grow and therefore more dependent on stock market returns to meet future income needs (with less ability to absorb a short-term sell-off in stocks).

Constant Percentage Method

If you are willing or able to risk varying (lower, especially) withdrawals from your portfolio month to month or year to year, there are other strategies to consider. One approach is withdrawing a constant, flat percentage of the portfolio each year. The 4% rule only sets the initial dollar amount withdrawn. After that, inflation determines how much you withdraw, regardless of how large a percentage of your portfolio the distribution represents.

With the “constant percentage” method, you withdraw a set percent of the portfolio each year. The dollar amount is determined by the portfolio value. The benefit of this strategy is that you are guaranteed to maintain some value in your retirement account—if your account goes down, your withdrawals will go down with it. The obvious drawback is that your distributions (the amount you can spend) can change in value drastically from year to year. For retirees that are dependent on a steady flow of cash, this can be an unacceptable risk. The amount you withdraw is not guaranteed to cover your expenses— periods of high inflation and relatively poor returns could result in an unrecoverable loss in your account and lower the bar on future withdrawals.

Probability of Failure

A newer approach uses thousands of modeled scenarios of asset returns and life expectancies, known as “Monte Carlo” simulations, to map out how a portfolio will perform throughout retirement. It then returns the maximum amount you can withdraw while maintaining the same acceptable rate of failure—which in this case would be running out of money. For this strategy to be most successful, you have to run the simulations each year to set your new withdrawal rate.

The result is that you will take out a small percentage of the portfolio at the beginning of retirement, but that percentage will increase as you age. This strategy has the benefit of conserving capital early in retirement, when poor market returns can have the most devastating impact on your nest egg. Distributions will not decrease as dramatically as they would under the constant percentage strategy during a bear market because the withdrawal percentage increases slightly each year to partially offset poor market returns.

The downside to the probability of failure strategy is that you’ll have less disposable income as you enter retirement— a time at which you may have the most desire to spend. It also requires expertise to run and interpret these simulations. There are free calculators out there and software you can purchase, but if the information you use to make your assumptions is bad, your real-world results may be equally bad. Because the stakes are high, we recommend consulting with a financial planning professional when using Monte Carlo simulations.

Despite the complexity of properly executing it, this strategy takes both market returns and your expected life span into account, affording it a depth that some of the other plans lack.

One-Size-Fits-All Funds

A number of companies, including Fidelity and Vanguard, have introduced mutual fund products that attempt to address the needs of investors looking for steady income in retirement. Fidelity’s solution is the Managed Retirement and Simplicity RMD suite of funds, which allow you to pick a time horizon (the year in the fund’s name) and then endeavor to pay you regular monthly income (the rate is adjusted each calendar year) through your target date, ending in a zero balance. Vanguard offers a Managed Allocation fund geared to investors already in retirement, which makes regular monthly payouts that are adjusted higher or lower by its managers at the start of each calendar year.

Unfortunately, these one-size-fits-all funds may be a poor fit for your individual goals. And if the funds’ managers fail to meet their income objectives, they’ll have to dip more deeply into your principal to pay the promised rate of income, compromising the amount you’ll receive in following years and possibly falling short of needs and expectations.

4% Rule vs Constant Percentage Method

TO HELP ILLUSTRATE how two of the plans we’ve discussed look in dollar terms over time, we’ve created two charts, one showing the 4% rule in action, the other a graph of how the constant percentage method might look. In both cases, we started with a hypothetical $1 million portfolio split 60/40 between stocks and bonds, using the returns of the S&P 500 index and the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, respectively, and calculated the values for the 33 years through 2021, rebalancing and taking a withdrawal at the start of each year. (It’s important to note that the two indexes are not investable and don’t charge fees, as mutual funds do.)

Take a look at the first chart below to see how a by-the-book 4% rule portfolio would have fared. Withdrawals started at 4% ($40,000) and were adjusted for inflation each year following. You can see that despite the ever-growing withdrawals (more than $85,000 by the end), the initial account value also continued to grow over the years, with the most sizable setbacks occurring as the tech bubble burst in the early 2000s and during the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. However, you’ll notice that even though the overall account value dipped significantly during those periods, the distribution rate continued to increase and traces a nearly straight ascending line from start to finish. This is one of the key benefits of the 4% rule.

The constant percentage chart looks a bit different. In this example, we withdrew 4% of the overall account value every year from start to finish. As you can see, the account ended up at only about half of that of the 4% Rule’s portfolio after 32 years, but the annual withdrawals rapidly increased in size and were more than twice as large by the end (more than $190,000). However, unlike the steady rate of distributions we saw in the first chart, here the withdrawal amounts varied from year to year, directly correlated to the underlying account’s performance, as market volatility had a much greater impact. But if you are interested in a greater amount of money to spend during retirement (at a detriment to the overall account’s value) and can stand the fluctuations in income, the constant percentage method is a possible solution.

Other ideas

Here are several other spending strategies to consider:

- IRS Life Expectancy Tables. Use the Internal Revenue Service’s life expectancy tables to help you determine an annual withdrawal amount that fits your expected life span. One simple means of doing this is to divide 1 by your remaining life expectancy to come up with an amount—for example, if your time horizon is 20 years, you’d withdraw 1/20th, or 5%, of your portfolio that year. The downside, from a planning perspective, would be to outlive that estimate and deplete your account too soon.

- Reverse Mortgage. You could supplement any investment and spending plan with a reverse mortgage and earn income from the value of your home. However, a reverse mortgage can be expensive upfront and often means you won’t be able to pass the home on to your heirs without significant financial strings attached.

- Stock Valuations. Some retirement planning specialists are using the markets’ stock valuations to determine annual withdrawal rates. As with some of the other methods, fluctuations in market values can result in significantly different amounts of income each year.

- Mix and Match. Of course, there is also the option of mixing and matching several of these strategies to achieve a degree of diversification in how you draw down your accounts, but this approach puts a lot of balls in the air to juggle month to month and year to year.

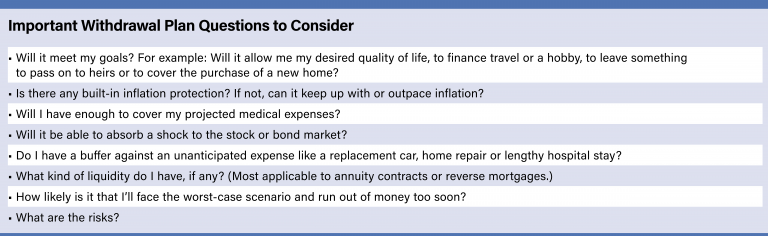

Which plan is right for you?

We have found there is no good one-size-fits-all spending plan. Our experience shows that a customized plan is far more effective and realistic than following a rigid, rule-based strategy that wasn’t designed to fit your particular concerns. At Adviser Investments, our goal is to help you achieve retirement peace of mind. Our financial planning professionals will work with you to find a strategy that best suits you and monitor your plan to ensure it continues to serve your needs.

This material is distributed for informational purposes only. The investment ideas and expressions of opinion may contain certain forward-looking statements and should not be viewed as recommendations or personal investment advice, or considered an offer to buy or sell specific securities. Data and statistics contained in this report are obtained from what we believe to be reliable sources; however, their accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Our statements and opinions are subject to change without notice and should be considered only as part of a diversified portfolio. You may request a free copy of the firm’s Form ADV Part 2, which describes, among other items, risk factors, strategies, affiliations, services offered and fees charged.

Past performance is not an indication of future returns. Tax, legal and insurance information contained herein is general in nature, is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal or tax advice, or as advice on whether to buy or surrender any insurance products. Personalized tax advice and tax return preparation is available through a separate, written engagement agreement with Adviser Investments Tax Solutions. We do not provide legal advice, nor sell insurance products. Always consult a licensed attorney, tax professional or licensed insurance professional regarding your specific legal or tax situation, or insurance needs.

© 2022 Adviser Investments, LLC. All Rights Reserved.